O BLESSED GLORIOUS TRINITY,

Bones to Philosophy, but milk to faith?

ON THE TRINITY

Chapter 121 | Love is the End of All the Commandments, and God Himself is Love.

Chapter 121. — Love is the End of All the Commandments, and God Himself is Love. All the commandments of God, then, are embraced in love, of which the apostle says: “Now the end of the commandment is charity, out of a pure heart, and of a good conscience, and of faith unfeigned.” Thus the end of every commandment is charity, that is, every commandment has love for its aim. But whatever is done either through fear of punishment or from some other carnal motive, and has not for its principle that love which the Spirit of God sheds abroad in the heart, is not done as it ought to be done, however it may appear to men. For this love embraces both the love of God and the love of our neighbor, and “on these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets,” 1324 we may add the Gospel and the apostles. For it is from these that we hear this voice: The end of the commandment is charity, and God is love. Wherefore, all God’s commandments, one ofwhich is, “Thou shalt not commit adultery,” and all those precepts which are not commandments but special counsels, one of which is, “It is good for a man not to touch a woman,” are rightly carried out only when the motive principle of action is the love of God, and the love of our neighbor in God. And this applies both to the present and the future life. We love God now by faith, then we shall love Him through sight. Now we love even our neighbor by faith; for we who are ourselves mortal know not the hearts of mortal men. But in the future life, the Lord “both will bring to light the hidden things of darkness, and will make manifest the counsels of the hearts, and then shall every man have praise of God;” for every man shall love and praise in his neighbor the virtue which, that it may not be hid, the Lord Himself shall bring to light. Moreover, lust diminishes as love grows, till the latter grows to such a height that it can grow no higher here. For “greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.” Who then can tell how great love shall be in the future world, when there shall be no lust for it to restrain and conquer? for that will be the perfection of health when there shall be no struggle with death.

Chapter 122. — Conclusion. But now there must be an end at last to this volume. And it is for yourself to judge whether you should call it a hand-book, or should use it as such. I, however, thinking that your zeal in Christ ought not to be despised, and believing and hoping all good of you in dependence on our Redeemer’s help, and loving you very much as one of the members of His body, have, to the best of my ability, written this book for you on Faith, Hope, and Love. May its value be equal to its length.

‘IMAGINATION’ mentioned 12 times in ON THE TRINITY

12 | The meaning of 12, which is considered a perfect number, is that it symbolizes God's power and authority, as well as serving as a perfect governmental foundation. It can also symbolize completeness or the nation of Israel as a whole. [“Mentioned” 0 times in Thus Spake Zarathustra]

How many things are now called the worst wickedness, which are only twelve feet broad and three months long!(?)

‘MADMAN’ mentioned 5 times in On the Catechising of the Uninstructed.

5 | The number of man because it represents the human 5 senses. Also understood as Grace.

‘MADMAN’ mentioned 1 time in THUS SPAKE ZARATHUSTRA

LVII [57]. THE CONVALESCENT. | One morning, not long after his return to his cave, Zarathustra sprang up from his couch like a madman, crying with a frightful voice, and acting as if some one still lay on the couch who did not wish to rise. Zarathustra’s voice also resounded in such a manner that his animals came to him frightened, and out of all the neighbouring caves and lurking-places all the creatures slipped away—flying, fluttering, creeping or leaping, according to their variety of foot or wing. Zarathustra, however, spake these words:

Up, abysmal thought out of my depth! I am thy cock and morning dawn, thou overslept reptile: Up! Up! My voice shall soon crow thee awake!

Unbind the fetters of thine ears: listen! For I wish to hear thee! Up! Up! There is thunder enough to make the very graves listen!

57 | Paul and the number 57 | One of the most eventful years in the Apostle Paul's long ministry was 57 A.D. It was in this year, during his third missionary journey, that he was chased out of Ephesus. A local pagan silversmith caused him to leave then he stirred up a riot against him (Acts 19)!

‘POWER’ mentioned 70 times in THUS SPAKE ZARATHUSTRA

70 | Symbolizes perfect spiritual order carried out with all power. It can also represent a period of judgment. Seventy (70) elders were appointed by Moses (Numbers 11:16). After reading the covenant God gave him to read to the people, Moses took 70 elders, along with Aaron and his sons, up Mount Sinai to have a special meal with God himself

“IMAGINATION”

Chapter 5. — The Trinity of the Outer Man, or of External Vision, is Not an Image of God.

The Trinity of the Outer Man, or of External Vision, is Not an Image of God. The Likeness of God is Desired Even in Sins. In External Vision the Form of the Corporeal Thing is as It Were the Parent, Vision the Offspring; But the Will that Unites These Suggests the Holy Spirit. Of What Kind We are to Reckon the Rest (Requies), and End (Finis), of the Will in Vision. There is Another Trinity in the Memory of Him Who Thinks Over Again [RUMINATION] What He Has Seen. Different Modes of Conceiving. Species is Produced by Species in Succession.3 The Imagination Also Adds Even to Things We Have Not Seen, Those Things Which We Have Seen Elsewhere. Number, Weight, Measure. After premising the difference between wisdom and knowledge, he points out 3a kind of trinity in that which is properly called knowledge; but one which, although we have reached in it the inner man, is not yet to be called the image of God. Of What Kind are the Outer and the Inner Man [E 3:16 | I pray that out of his glorious riches he may strengthen you with power through his Spirit in your inner being,]

2[67] | ‘I’ “subject” as horizon line. Reversal of perspectival gaze.

Chapter 2. — Every Corporeal Conception Must Be Rejected, in Order that It May Be Understood How God is Truth.

For when we aspire from this depth to that height, it is a step towards no small knowledge, if, before we can know what God is, we can already know what He is not. For certainly He is neither earth nor heaven; nor, as it were, earth and heaven; nor any such thing as we see in the heaven; nor any such thing as we do not see, but which perhaps is in heaven. Neither if you were to magnify in the imagination of your thought the light of the sun as much as you are able, either that it may be greater, or that it may be brighter, a thousand times as much, or times without number; neither is this God. Neither as we think of the pure angels as spirits animating celestial bodies, and changing and dealing with them after the will by which they serve God; not even if all, and there are “thousands of thousands,” were brought together into one, and became one; neither is any such thing God. Neither if you were to think of the same spirits as without bodies — a thing indeed most difficult for carnal thought to do. Behold and see, if thou canst, O soul pressed down by the corruptible body, and weighed down by earthly thoughts, many and various; behold and see, if thou canst, that God is truth. 664 For it is written that “God is light;” 665 not in such way as these eyes see, but in such way as the heart sees, when it is said, He is truth [reality] . Ask not what is truth [reality] for immediately the darkness of corporeal images and the clouds of phantasms will put themselves in the way, and will disturb that calm which at the first twinkling shone forth to thee, when I said truth [reality] . See that thou remainest, if thou canst, in that first twinkling with which thou art dazzled, as it were, by a flash, when Every Corporeal Conception Must Be Rejected, in Order that It May Be Understood. . . it is said to thee, Truth [Reality]. But thou canst not; thou wilt glide back into those usual and earthly things. And what weight, pray, is it that will cause thee so to glide back, unless it be the bird-lime of the stains of appetite thou hast contracted, and the errors of thy wan- dering from the right path?

Chapter 4. — How This Unity Comes to Pass.

7. But if that will which moves to and fro, hither and thither, the eye that is to be in- formed, and unites it when formed, shall have wholly converged to the inward phantasy, and shall have absolutely turned the mind’s eye from the presence of the bodies which lie around the senses, and from the very bodily senses themselves, and shall have wholly turned it to that image, which is perceived within; then so exact a likeness of the bodily species ex- pressed from the memory is presented, that not even reason itself is permitted to discern whether the body itself is seen without, or only something of the kind thought of within. For men sometimes either allured or frightened by over-much thinking of visible things, have even suddenly uttered words accordingly, as if in real fact they were engaged in the very midst of such actions or sufferings. And I remember some one telling me that he was wont to perceive in thought, so distinct and as it were solid, a form of a female body, as to be moved, as though it were a reality. Such power has the soul over its own body, and such influence has it in turning and changing the quality of its [corporeal] garment; just as a man may be affected when clothed, to whom his clothing sticks. It is the same kind of affection, too, with which we are beguiled through imaginations in sleep. But it makes a very great difference, whether the senses of the body are lulled to torpor, as in the case of sleepers, or disturbed from their inward structure, as in the case of madmen, or distracted in some other mode, as in that of diviners or prophets; and so from one or other of these causes, the intention of the mind is forced by a kind of necessity upon those images which occur to it, either from memory, or by some other hidden force through certain spiritual commixtures of a similarly spiritual substance: or whether, as sometimes happens to people in health and awake, that the will occupied by thought turns itself away from the senses, and so informs the eye of the mind by various images of sensible things, as though those sensible things themselves were actually perceived.

The Imagination Also Adds Even to Things We Have Not Seen, Those Things...

XLII. (42) REDEMPTION | It is, however, the smallest thing unto me since I have been amongst men, to see one person lacking an eye, another an ear, and a third a leg, and that others have lost the tongue, or the nose, or the head.

I see and have seen worse things, and divers things so hideous, that I should neither like to speak of all matters, nor even keep silent about some of them: namely, men who lack everything, except that they have too much of one thing—men who are nothing more than a big eye, or a big mouth, or a big belly, or something else big,—reversed cripples, I call such men.

42 | The number 42 is always associated with suffering and the duration of time the suffering will last.

the NEITHINKERS GUIDE to the GALAXYZ

Chapter 10. — The Imagination Also Adds Even to Things We Have Not Seen, Those Things Which We Have Seen Elsewhere.

And therefore, in conceiving conjointly, what we remember to have seen singly, we seem not to conceive that which we remember; while we really do this under the law of the memory, whence we take everything which we join together after our own pleasure in manifold and diverse ways. For we do not conceive even the very magnitudes of bodies, which magnitudes we never saw, without help of the memory; for the measure of space to which our gaze commonly reaches through the magnitude of the world, is the measure also to which we enlarge the bulk of bodies, whatever they may be, when we conceive them as great as we can. And reason, indeed, proceeds still beyond, but phantasy does not follow her; as when reason announces the infinity of number also, which no vision of him who conceives according to corporeal things can apprehend. The same reason also teaches that the most minute atoms are infinitely divisible; yet when we have come to those slight and minute particles which we remember to have seen, then we can no longer behold phantasms more slender and more minute, although reason does not cease to continue to divide them. So we conceive no corporeal things, except either those we re- member, or from those things which we remember.

"On The Holy Trinity St. Augustine Treaties"

The Creature is Not So Taken by the Holy Spirit as Flesh is by the Word

Chapter 6. — The Creature is Not So Taken by the Holy Spirit as Flesh is by the Word.

Accordingly, although that dove is called the Spirit; and in speaking of that fire, “There appeared unto them,” he says, “cloven tongues, like as of fire, and it sat upon each of them; and they began to speak with other tongues, as the Spirit gave them utterance; in order to show that the Spirit was manifested by that fire, as by the dove; yet we cannot call the Holy Spirit both God and a dove, or both God and fire, in the same way as we call the Son both God and man; nor as we call the Son the Lamb of God; which not only John the Baptist says, “Behold the Lamb of God,” but also John the Evangelist sees the Lamb slain in the Apocalypse.

For that prophetic vision was not shown to bodily eyes through bodily forms, but in the spirit through spiritual images of bodily things. But whosoever saw that dove and that fire, saw them with their eyes. Although it may perhaps be disputed concerning the fire, whether it was seen by the eyes or in the spirit, on account of the form of the sentence. For the text does not say, They saw cloven tongues like fire, but, “THERE APPEARED TO THEM.” But we are not wont to say with the same meaning, It appeared to me; as we say, I saw. And in those spiritual visions of corporeal images the usual expressions are, both, It appeared to me; and, I saw: but in those things which are shown to the eyes through express corporeal forms, the common expression is not, It appeared to me; but, I saw.

There may, therefore, be a question raised respecting that fire, how it was seen; whether within in the spirit as it were outwardly, or really outwardly before the eyes of the flesh. But of that dove, which is said to have descended in a bodily form, no one ever doubted that it was seen by the eyes. Nor, again, as we call the Son a Rock (for it is written, “And that Rock was Christ” )[LXI. THE HONEY SACRIFICE | On an Eternal Ground, on Hard Primary Rock, on this Highest, Hardest, Primary Mountain-Ridge ], can we so call the Spirit a dove or fire. For that rock was a thing already created, and after the mode of its action was called by the name of Christ, whom it signified; like the stone placed under Jacob’s head, and also anointed, which he took in order to signify the Lord ; 254 or as Isaac was Christ, when he carried the wood for the sacrifice of himself. A particular significative action was added to those already existing things; they did not, as that dove and fire, suddenly come into being in order simply so to signify. The dove and the fire, indeed, seem to me more like that flame which appeared to Moses in the bush, or that pillar which the people followed in the wilderness, or the thunders and lightnings which came when the Law was given in the mount.

For the corporeal form of these things came into being for the very purpose, that it might signify something, and then pass away.

― “conversely, even those philosophers and religious people who had the most compelling grounds in their logic and piety to take their corporeality as a deception, and indeed as an overcome and dispensed-with deception, were not able to avoid recognising the stupid fact that the body has not gone away: for which the most remarkable testimony is to be found partly in Paul, partly in the Vedanta philosophy”. [1]

[1] Paul: breadth, and length, and depth, and height; Vedanta: गाय - “Gaya”

The Opinions of Philosophers Respecting the Substance of the Soul. The Error...

Chapter 7. — The Opinions of Philosophers Respecting the Substance of the Soul.

The Error of Those Who are of Opinion that the Soul is Corporeal, Does Not Arise from Defective Knowledge of the Soul, But from Their Adding There to Something Foreign to It. What is Meant by Finding.

9. For as to that fifth kind of body, I know not what, which some have added to the four well-known elements of the world, and have said that the soul was made of this, I do not think we need spend time in discussing it in this place. For either they mean by body what we mean by it, viz., that of which a part is less than the whole in extension of place, and they are to be reckoned among those who have believed the mind to be corporeal: or if they call either all substance, or all changeable substance, body, whereas they know that not all substance is contained in extension of place by any length and breadth and height, we need not contend with them about a question of words.

THE TREE ON THE HILL. (Town: Pied Cow)

“This tree standeth lonely here on the hills; it hath grown up high above man and beast.

And if it wanted to speak, it would have none who could understand it: so high hath it grown.

Now it waiteth and waiteth,—for what doth it wait? It dwelleth too close to the seat of the clouds; it waiteth perhaps for the first lightning?”

When Zarathustra had said this, the youth called out with violent gestures: “Yea, Zarathustra, thou speakest the truth. My destruction I longed for, when I desired to be on the height, and thou art the lightning for which I waited! Lo! what have I been since thou hast APPEARED amongst us? It is mine envy of thee that hath destroyed me!”—Thus spake the youth, and wept bitterly. Zarathustra, however, put his arm about him, and led the youth away with him.

"On The Holy Trinity St. Augustine Treaties"

Chapter 13. — The Death of Christ Voluntary. How the Mediator of Life Subdued the Mediator of Death. How the Devil Leads His Own to Despise the Death of Christ.

The consummating death I show unto you, which becometh a stimulus and promise to the living.

His death, dieth the consummating one triumphantly, surrounded by hoping and promising ones.

Thus should one learn to die; and there should be no festival at which such a dying one doth not consecrate the oaths of the living!

Thus to die is best; the next best, however, is to die in battle, and sacrifice a great soul.

But to the fighter equally hateful as to the victor, is your grinning death which stealeth nigh like a thief,—and yet cometh as master.

My death, praise I unto you, the voluntary death, which cometh unto me because I want it.

And when shall I want it?—He that hath a goal and an heir, wanteth death at the right time for the goal and the heir.

And out of reverence for the goal and the heir, he will hang up no more withered wreaths in the sanctuary of life.

Verily, not the rope-makers will I resemble: they lengthen out their cord, and thereby go ever backward.

21 | THUS SPAKE ZARATHUSTRA - VOLUNTARY DEATH.

"On The Holy Trinity St. Augustine Treaties"

17. …And so the devil, in that very death of the flesh, lost man, whom he was possessing as by an absolute right, seduced as he was by his own consent, [When he was just midway across, the little door opened once more, and a gaudily-dressed fellow like a buffoon sprang out, and went rapidly after the first one.] and over whom he ruled, himself impeded by no corruption of flesh and blood, through that frailty of man’s mortal body, whence he was both too poor and too weak; he who was proud in proportion as he was, as it were, both richer and stronger, ruling over him who was, as it were, both clothed in rags and full of troubles. For whither he drove the sinner to fall, himself not following, there by following he compelled the Redeemer to descend. And so the Son of God deigned to become our friend in the fellowship of death, to which because he came not, the enemy thought himself to be better and greater than ourselves. For our Redeemer says, “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends .”

Wherefore also the devil thought himself superior to the Lord Himself, inasmuch as the Lord in His sufferings yielded to him; for of Him, too, is understood what is read in the Psalm, “For Thou hast made Him a little lower than the angels :” so that He, being Himself put to death, although innocent, by the unjust one acting against us as it were by just right, might by a most just right overcome him, and so might lead captive the captivity wrought through sin, and free us from a captivity that was just on account of sin, by blotting out the handwriting, and redeeming us who were to be justified although sinners, through His own righteous blood unrighteously poured out.

What dost thou here between the towers? In the tower is the place for thee, thou shouldst be locked up; to one better than thyself thou blockest the way!”

ZARATHUSTRA’S PROLOGUE.

LXIX. THE SHADOW (The Camel)

[50 + 10 + (10 - 1) = 69]

With thee have I pushed into all the forbidden, all the worst and the furthest: and if there be anything of virtue in me, it is that I have had no fear of any prohibition.

With thee have I broken up whatever my heart revered; all boundary-stones and statues have I o’erthrown; the most dangerous wishes did I pursue,—verily, beyond every crime did I once go.

With thee did I unlearn the belief in words and worths and in great names. When the devil casteth his skin, doth not his name also fall away? It is also skin. The devil himself is perhaps—skin.

‘Nothing is true, all is permitted’ [seduced as he was by his own consent]: so said I to myself. Into the coldest water did I plunge with head and heart. Ah, how oft did I stand there naked on that account, like a red crab!

Ah, where have gone all my goodness and all my shame and all my belief in the good! Ah, where is the lying innocence which I once possessed, the innocence of the good and of their noble lies!

Too oft, verily, did I follow close to the heels of truth: then did it kick me on the face. Sometimes I meant to lie, and behold! then only did I hit—the truth.

Too much hath become clear unto me: now it doth not concern me any more. Nothing liveth any longer that I love,—how should I still love myself?

‘To live as I incline, or not to live at all’: so do I wish; so wisheth also the holiest. But alas! how have I still—inclination?

Have I—still a goal? A haven towards which MY sail is set?

A good wind? Ah, he only who knoweth WHITHER he saileth, knoweth what wind is good, and a fair wind for him.

What still remaineth to me? A heart weary and flippant; an unstable will; fluttering wings; a broken backbone.

This seeking for MY home: O Zarathustra, dost thou know that this seeking hath been MY home-sickening; it eateth me up. [2[67] | Saddle us with nicknames that eat their way into not only our skin?]

‘WHERE is—MY home?’ For it do I ask and seek, and have sought, but have not found it. O eternal everywhere, O eternal nowhere, O eternal—in-vain!”

Thus spake the shadow [“Good Europeans” :“The man who is restless, who is homeless, who is a wanderer, he has forgotten how to love his people because he loves many peoples, the good European.”], and Zarathustra’s countenance lengthened at his words. “Thou art my shadow!” said he at last sadly.

“Thy danger is not small, thou free spirit and wanderer! Thou hast had a bad day: see that a still worse evening doth not overtake thee!

To such unsettled ones as thou, seemeth at last even a prisoner blessed. Didst thou ever see how captured criminals sleep? They sleep quietly, they enjoy their new security.

Beware lest in the end a narrow faith capture thee, a hard, rigorous delusion! For now everything that is narrow and fixed seduceth and tempteth thee.

"On The Holy Trinity St. Augustine Treaties"

351 | Why, When All Will to Be Blessed, that is Rather Chosen by Which One Withdraws...

Chapter 6. — Why, When All Will to Be Blessed, that is Rather Chosen by Which One Withdraws from Being So.

9. Since, then, a blessed life consists of these two things, and is known to all, and dear to all; what can we think to be the cause why, when they cannot have both, men choose, out of these two, to have all things that they will, rather than to will all things well, even although they do not have them? Is it the depravity itself of the human race, in such wise that, while they are not unaware that neither is he blessed who has not what he wills, nor he who has what he wills wrongly, but he who both has whatsoever good things he wills, and wills no evil ones, yet, when both are not granted of those two things in which the blessed life consists, that is rather chosen by which one is withdrawn the more from a blessed life (since he cer- tainly is further from it who obtains things which he wickedly desired, than he who only does not obtain the things which he desired); whereas the good will ought rather to be chosen, and to be preferred, even if it do not obtain the things which it seeks? For he comes near to being a blessed man, who wills well whatsoever he wills, and wills things, which when he obtains, he will be blessed. And certainly not bad things, but good, make men blessed, when they do so make them. And of good things he already has something, and that, too, a something not to be lightly esteemed, — namely, the very good will itself; who longs to rejoice in those good things of which human nature is capable, and not in the per- formance or the attainment of any evil; and who follows diligently, and attains as much as he can, with a prudent, temperate, courageous, and right mind, such good things as are possible in the present miserable life ; so as to be good even in evils, and when all evils have been put an end to, and all good things fulfilled, then to be blessed. [COMPARE /CONTRAST WITH: “The Good European”; Spiritually Conscientious One, Soothsayer, Saint in Forest - (AUGUSTINE - He himself found I no longer when I found his cot—but two wolves found I therein)]

ZARATHUSTRA’S PROLOGUE (The Lion)

To create itself freedom, and give a holy Nay even unto duty: for that, my brethren, there is need of the lion.

To assume the right to new values—that is the most formidable assumption for a load-bearing and reverent spirit. Verily, unto such a spirit it is preying, and the work of a beast of prey.

As its holiest, it once loved “Thou-shalt”: now is it forced to find illusion and arbitrariness even in the holiest things, that it may capture freedom from its love: the lion is needed for this capture.*

But tell me, my brethren, what the child can do, which even the lion could not do? Why hath the preying lion still to become a child?

Innocence is the child, and forgetfulness, a new beginning, a game, a self-rolling wheel, a first movement, a holy Yea.

Aye, for the game of creating, my brethren, there is needed a holy Yea unto life: ITS OWN will, willeth now the spirit; HIS OWN world winneth the world’s outcast.

*The same thing is also witnessed by the lion, but only half as much; For he is blind in one eye.

“To speak before three eyes,” said the old pope cheerfully (he was blind of one eye)

(clear sight; eye of love and eye of hate).

READING AND WRITING. (The Present, the Populous)

Of all that is written, I love only what a person hath written with his blood. Write with blood, and thou wilt find that blood is spirit.

It is no easy task to understand unfamiliar blood; I hate the reading idlers.

He who knoweth the reader, doeth nothing more for the reader. Another century of readers—and spirit itself will stink.

Every one being allowed to learn to read, ruineth in the long run not only writing but also thinking.

Once spirit was God, then it became man, and now it even becometh populace.

He that writeth in blood and proverbs doth not want to be read, but learnt by heart.

In the mountains the shortest way is from peak to peak, but for that route thou must have long legs. Proverbs should be peaks, and those spoken to should be big and tall.

"On The Holy Trinity St. Augustine Treaties"

18. Hence also the devil mocks those who are his own until this very day, to whom he presents himself as a false mediator, as though they would be cleansed or rather entangled and drowned by his rites [ZARATHUSTRA’S PROLOGUE | he threw his pole away, and shot downwards faster than it, like an eddy of arms and legs, into the depth], in that he very easily persuades the proud to ridicule and despise the death of Christ, from which the more he himself is estranged, the more is he believed by them to be the holier and more divine.

Chapter 9. — Of the Term “Enigma,” And of Tropical Modes of Speech. What has been said relates to the words of the apostle, that “we see now through a glass;” but whereas he has added, “in an enigma,” the meaning of this addition is unknown to any who are unacquainted with the books that contain the doctrine of those modes of speech, which the Greeks call Tropes, which Greek word we also use in Latin. For as we more commonly speak of schemata than of figures, so we more commonly speak of tropes than of modes. And it is a very difficult and uncommon thing to express the names of the several modes or tropes in Latin, so as to refer its appropriate name to each. And hence some Latin translators, through unwillingness to employ a Greek word, where the apostle says, “Which things are an allegory,” have rendered it by a circumlocution — Which things signify one thing by another. But there are several species of this kind of trope that is called allegory, and one of them is that which is called enigma. Now the definition of the generic term must necessarily embrace also all its species; and hence, as every horse is an animal, but not every animal is a horse, so every enigma is an allegory, but every allegory is not an enigma. What then is an allegory, but a trope wherein one thing is understood from another? as in the Epistle to the Thessalonians, “Let us not therefore sleep, as do others; but let us watch and be sober: for they who sleep, sleep in the night; and they who are drunken, are drunken in the night: but let us who are of the day, be sober.” But this allegory is not an enigma. For here the meaning is patent to all but the very dull; but an enigma is, to explain it briefly, an obscure allegory, as, e.g., “The horseleech had three daughters,” [ XLI. THE SOOTHSAYER | Brightness of midnight was ever around me; lonesomeness cowered beside her; and as a third, death-rattle stillness, the worst of my female friends. ]and other like instances. But when the apostle spoke of an allegory, he does not find it in the words, but in the fact; since he has shown that the two Testaments are to be understood by the two sons of Abraham, one by a bondmaid, and the other by a free woman, which was a thing not said, but also done. And before this was explained, it was obscure; and accordingly such an allegory, which is the generic name, could be specifically called an enigma.

XLVI. THE VISION AND THE ENIGMA.

1 | When it got abroad among the sailors that Zarathustra was on board the ship [Disciple whom he loved most | “The good Europeans – tells stories of accidents at sea. (favorite disciple)” 31[11][1] “Good Europeans” | “The man who is restless, who is homeless, who is a wanderer, he has forgotten how to love his people because he loves many peoples, the good European.”] —for a man who came from the Happy Isles had gone on board along with him,—there was great curiosity and expectation. But Zarathustra kept silent for two days, and was cold and deaf with sadness; so that he neither answered looks nor questions. On the evening of the second day, however, he again opened his ears, though he still kept silent: for there were many curious and dangerous things to be heard on board the ship, which came from afar, and was to go still further. Zarathustra, however, was fond of all those who make distant voyages, and dislike to live without danger. And behold! when listening, his own tongue was at last loosened, and the ice of his heart broke. Then did he begin to speak thus:

To you, the daring venturers and adventurers, and whoever hath embarked with cunning sails upon frightful seas,—

To you the enigma-intoxicated, the twilight-enjoyers, whose souls are allured by flutes to every treacherous gulf:

—For ye dislike to grope at a thread with cowardly hand; and where ye can DIVINE, there do ye hate to CALCULATE—

To you only do I tell the enigma that I SAW—the vision of the lonesomest one.—

Gloomily walked I lately in corpse-coloured twilight—gloomily and sternly, with compressed lips. Not only one sun had set for me.

A path which ascended daringly among boulders, an evil, lonesome path, which neither herb nor shrub any longer cheered, a mountain-path, crunched under the daring of my foot.

Mutely marching over the scornful clinking of pebbles, trampling the stone that let it slip: thus did my foot force its way upwards.

Upwards:—in spite of the spirit that drew it downwards, towards the abyss, the spirit of gravity, my devil and arch-enemy.

Upwards:—although it sat upon me, half-dwarf, half-mole; paralysed, paralysing; dripping lead in mine ear, and thoughts like drops of lead into my brain.

“O Zarathustra,” it whispered scornfully, syllable by syllable, “thou stone of wisdom! Thou threwest thyself high, but every thrown stone must—fall!

O Zarathustra, thou stone of wisdom, thou sling-stone, thou star-destroyer! Thyself threwest thou so high,—but every thrown stone—must fall!

Condemned of thyself, and to thine own stoning: O Zarathustra, far indeed threwest thou thy stone—but upon THYSELF will it recoil!”

Then was the dwarf silent; and it lasted long. The silence, however, oppressed me; and to be thus in pairs, one is verily lonesomer than when alone!

I ascended, I ascended, I dreamt, I thought,—but everything oppressed me. A sick one did I resemble, whom bad torture wearieth, and a worse dream reawakeneth out of his first sleep.—

But there is something in me which I call courage: it hath hitherto slain for me every dejection. This courage at last bade me stand still and say: “Dwarf! Thou! Or I!”—

For courage is the best slayer,—courage which ATTACKETH: for in every attack there is sound of triumph.

Man, however, is the most courageous animal: thereby hath he overcome every animal. With sound of triumph hath he overcome every pain; human pain, however, is the sorest pain.

Courage slayeth also giddiness at abysses: and where doth man not stand at abysses! Is not seeing itself—seeing abysses?

Courage is the best slayer: courage slayeth also fellow-suffering. Fellow-suffering, however, is the deepest abyss: as deeply as man looketh into life, so deeply also doth he look into suffering.

Courage, however, is the best slayer, courage which attacketh: it slayeth even death itself; for it saith: “WAS THAT life? Well! Once more!”

In such speech, however, there is much sound of triumph. He who hath ears to hear, let him hear.—

2 | “Halt, dwarf!” said I. “Either I—or thou! I, however, am the stronger of the two:—thou knowest not mine abysmal thought! IT—couldst thou not endure!”

Then happened that which made me lighter: for the dwarf sprang from my shoulder, the prying sprite! And it squatted on a stone in front of me. There was however a gateway just where we halted.

“Look at this gateway! Dwarf!” I continued, “it hath two faces. Two roads come together here: these hath no one yet gone to the end of.

This long lane backwards: it continueth for an eternity. And that long lane forward—that is another eternity.

They are antithetical to one another, these roads; they directly abut on one another:—and it is here, at this gateway, that they come together. The name of the gateway is inscribed above: ‘This Moment.’

But should one follow them further—and ever further and further on, thinkest thou, dwarf, that these roads would be eternally antithetical?”—

“Everything straight lieth,” murmured the dwarf, contemptuously. “All truth is crooked; time itself is a circle.”

“Thou spirit of gravity!” said I wrathfully, “do not take it too lightly! Or I shall let thee squat where thou squattest, Haltfoot,—and I carried thee HIGH!”

“Observe,” continued I, “This Moment! From the gateway, This Moment, there runneth a long eternal lane BACKWARDS: behind us lieth an eternity.

Must not whatever CAN run its course of all things, have already run along that lane? Must not whatever CAN happen of all things have already happened, resulted, and gone by?

And if everything have already existed, what thinkest thou, dwarf, of This Moment? Must not this gateway also—have already existed?

And are not all things closely bound together in such wise that This Moment draweth all coming things after it? CONSEQUENTLY—itself also?

For whatever CAN run its course of all things, also in this long lane OUTWARD—MUST it once more run!—

And this slow spider which creepeth in the moonlight, and this moonlight itself, and thou and I in this gateway whispering together, whispering of eternal things—must we not all have already existed?

—And must we not return and run in that other lane out before us, that long weird lane—must we not eternally return?”—

Thus did I speak, and always more softly: for I was afraid of mine own thoughts, and arrear-thoughts. Then, suddenly did I hear a dog HOWL near me.

Had I ever heard a dog howl thus? My thoughts ran back. Yes! When I was a child, in my most distant childhood:

—Then did I hear a dog howl thus. And saw it also, with hair bristling, its head upwards, trembling in the stillest midnight, when even dogs believe in ghosts:

—So that it excited my commiseration. For just then went the full moon, silent as death, over the house; just then did it stand still, a glowing globe—at rest on the flat roof, as if on some one’s property:—

Thereby had the dog been terrified: for dogs believe in thieves and ghosts. And when I again heard such howling, then did it excite my commiseration once more.

Where was now the dwarf? And the gateway? And the spider? And all the whispering? Had I dreamt? Had I awakened? ‘Twixt rugged rocks did I suddenly stand alone, dreary in the dreariest moonlight.

BUT THERE LAY A MAN! [HUME DOGMATIC SLUMBER] And there! The dog leaping, bristling, whining—now did it see me coming—then did it howl again, then did it CRY:—had I ever heard a dog cry so for help?

And verily, what I saw, the like had I never seen. A young shepherd did I see, writhing, choking, quivering, with distorted countenance, and with a heavy black serpent hanging out of his mouth.

Had I ever seen so much loathing and pale horror on one countenance? He had perhaps gone to sleep? Then had the serpent crawled into his throat—there had it bitten itself fast.

My hand pulled at the serpent, and pulled:—in vain! I failed to pull the serpent out of his throat. Then there cried out of me: “Bite! Bite!

Its head off! Bite!”—so cried it out of me; my horror, my hatred, my loathing, my pity, all my good and my bad cried with one voice out of me.—

Ye daring ones around me! Ye venturers and adventurers, and whoever of you have embarked with cunning sails on unexplored seas! Ye enigma-enjoyers!

Solve unto me the enigma that I then beheld, interpret unto me the vision of the lonesomest one!

For it was a vision and a foresight:—WHAT did I then behold in parable? And WHO is it that must come some day?

WHO is the shepherd into whose throat the serpent thus crawled? WHO is the man into whose throat all the heaviest and blackest will thus crawl? [The Dream Interpreter | Who is [not] ‘Joseph’ Today? And Why?]

—The shepherd however bit as my cry had admonished him; he bit with a strong bite! Far away did he spit the head of the serpent—: and sprang up.—

No longer shepherd, no longer man—a transfigured being, a light-surrounded being, that LAUGHED! Never on earth laughed a man as HE laughed!

O my brethren, I heard a laughter which was no human laughter,—and now gnaweth a thirst at me, a longing that is never allayed.

My longing for that laughter gnaweth at me: oh, how can I still endure to live! And how could I endure to die at present!—

Thus spake Zarathustra.

‘EAGLE’ mentioned 30 times in THUS SPAKE ZARATHUSTRA

30 | The prophet Ezekiel begins his book of the same name in the thirtieth year (which likely referenced his age at the time - Ezekiel 1:1). It is at this time he receives his first recorded vision from God, known as the "wheel in the middle of a wheel" or "wheel within a wheel" vision.

His book of the same name in the thirtieth year | “Zarathustra born on lake Urmi; left his home in his thirtieth year, went into the province of Aria [modern day AFGHANISTAN], and, during ten years of solitude in the mountains, composed the Zend-Avesta.”[1] His autobiographical sketch: “Ecce Homo”, It would even be possible to consider all ‘Zarathustra’ as a musical composition.”

Ezekiel 1:1-48:22

* * *

4-9 I looked: I saw an immense dust storm come from the north, an immense cloud with lightning flashing from it, a huge ball of fire glowing like bronze. Within the fire were what looked like four creatures vibrant with life. Each had the form of a human being, but each also had four faces and four wings. Their legs were as sturdy and straight as columns, but their feet were hoofed like those of a calf and sparkled from the fire like burnished bronze. On all four sides under their wings they had human hands. All four had both faces and wings, with the wings touching one another. They turned neither one way nor the other; they went straight forward.

10-12 Their faces looked like this: In front a human face, on the right side the face of a lion, on the left the face of an ox, and in back the face of an eagle. So much for the faces. The wings were spread out with the tips of one pair touching the creature on either side; the other pair of wings covered its body. Each creature went straight ahead. Wherever the spirit went, they went. They didn’t turn as they went.

13-14 The four creatures looked like a blazing fire, or like fiery torches. Tongues of fire shot back and forth between the creatures, and out of the fire, bolts of lightning. The creatures flashed back and forth like strikes of lightning.

15-16 As I watched the four creatures, I saw something that looked like a wheel on the ground beside each of the four-faced creatures. This is what the wheels looked like: They were identical wheels, sparkling like diamonds in the sun. It looked like they were wheels within wheels, like a gyroscope.

17-21 They went in any one of the four directions they faced, but straight, not veering off. The rims were immense, circled with eyes. When the living creatures went, the wheels went; when the living creatures lifted off, the wheels lifted off. Wherever the spirit went, they went, the wheels sticking right with them, for the spirit of the living creatures was in the wheels. When the creatures went, the wheels went; when the creatures stopped, the wheels stopped; when the creatures lifted off, the wheels lifted off, because the spirit of the living creatures was in the wheels. [XVII. THE WAY OF THE CREATING ONE | Art thou a new strength and a new authority? A first motion? A self-rolling wheel? Canst thou also compel stars to revolve around thee?]

22-24 Over the heads of the living creatures was something like a dome, shimmering like a sky full of cut glass, vaulted over their heads. Under the dome one set of wings was extended toward the others, with another set of wings covering their bodies. When they moved I heard their wings—it was like the roar of a great waterfall, like the voice of The Strong God, like the noise of a battlefield. When they stopped, they folded their wings.

25-28 And then, as they stood with folded wings, there was a voice from above the dome over their heads. Above the dome there was something that looked like a throne, sky-blue like a sapphire, with a humanlike figure towering above the throne. From what I could see, from the waist up he looked like burnished bronze and from the waist down like a blazing fire. Brightness everywhere! The way a rainbow springs out of the sky on a rainy day—that’s what it was like. It turned out to be the Glory of God!

When I saw all this, I fell to my knees, my face to the ground. Then I heard a voice.

***

2 It said, “Son of man, stand up. I have something to say to you.”

2 The moment I heard the voice, the Spirit entered me and put me on my feet. As he spoke to me, I listened.

3-7 He said, “Son of man, I’m sending you to the family of Israel, a rebellious nation if there ever was one. They and their ancestors have fomented rebellion right up to the present. They’re a hard case, these people to whom I’m sending you—hardened in their sin. Tell them, ‘This is the Message of God, the Master.’ They are a defiant bunch. Whether or not they listen, at least they’ll know that a prophet’s been here. But don’t be afraid of them, son of man, and don’t be afraid of anything they say. Don’t be afraid when living among them is like stepping on thorns or finding scorpions in your bed. Don’t be afraid of their mean words or their hard looks. They’re a bunch of rebels. Your job is to speak to them. Whether they listen is not your concern. They’re hardened rebels.

8 “Only take care, son of man, that you don’t rebel like these rebels. Open your mouth and eat what I give you.”

9-10 When I looked he had his hand stretched out to me, and in the hand a book, a scroll. He unrolled the scroll. On both sides, front and back, were written lamentations and mourning and doom.

Warn These People

3 He told me, “Son of man, eat what you see. Eat this book. Then go and speak to the family of Israel.”

2-3 As I opened my mouth, he gave me the scroll to eat, saying, “Son of man, eat this book that I am giving you. Make a full meal of it!”

So I ate it. It tasted so good—just like honey.

—LXI. THE HONEY SACRIFICE. “O Zarathustra,” said they, “gazest thou out perhaps for thy happiness?”—“Of what account is my happiness!” answered he, “I have long ceased to strive any more for happiness, I strive for my work.”—“O Zarathustra,” said the animals once more, “that sayest thou as one who hath overmuch of good things. Liest thou not in a SKY-BLUE lake of happiness?”—“Ye wags,” answered Zarathustra, and smiled, “how well did ye choose the simile! But ye know also that my happiness is heavy, and not like a fluid wave of water: it presseth me and will not leave me, and is like molten pitch.”—

LVII. THE CONVALESCENT | How charming it is that there are words and [गाय] tones; are not words and tones rainbows and seeming bridges ‘twixt the eternally separated?

To each soul belongeth another world; to each soul is every other soul a back-world.

Among the most alike doth semblance deceive most delightfully: for the smallest gap is most difficult to bridge over.

For me—how could there be an outside-of-me? There is no outside! But this we forget on hearing tones; how delightful it is that we forget!

Have not names and tones been given unto things that man may refresh himself with them? It is a beautiful folly, speaking; therewith danceth man over everything.

How lovely is all speech and all falsehoods of tones! With tones danceth our love on variegated rainbows.—

—“O Zarathustra,” said then his animals, “to those who think like us, things all dance themselves: they come and hold out the hand and laugh and flee—and return.

Everything goeth, everything returneth; eternally rolleth the wheel of existence. Everything dieth, everything blossometh forth again; eternally runneth on the year of existence.

Everything breaketh, everything is integrated anew; eternally buildeth itself the same house of existence. All things separate, all things again greet one another; eternally true to itself remaineth the ring of existence.

Every moment beginneth existence, around every ‘Here’ rolleth the ball ‘There.’ The middle is everywhere. Crooked is the path of eternity.”—

—O ye wags and barrel-organs! answered Zarathustra, and smiled once more, how well do ye know what had to be fulfilled in seven days:—

—And how that monster crept into my throat and choked me! But I bit off its head and spat it away from me.

And ye—ye have made a lyre-lay out of it? Now, however, do I lie here, still exhausted with that biting and spitting-away, still sick with mine own salvation.

(LXXV. SCIENCE | Thus sang the magician; and all who were present went like birds unawares into the net of his artful and melancholy voluptuousness. Only the spiritually conscientious one had not been caught: he at once snatched the harp from the magician and called out: “Air! Let in good air! Let in Zarathustra! Thou makest this cave sultry and poisonous, thou bad old magician!

LXXVI. AMONG DAUGHTERS OF THE DESERT Thus spake the wanderer who called himself Zarathustra’s shadow; and before any one answered him, he had seized the harp of the old magician, crossed his legs, and looked calmly and sagely around him:—with his nostrils, however, he inhaled the air slowly and questioningly, like one who in new countries tasteth new foreign air. Afterward he began to sing with a kind of roaring.)

‘Lyre’ mentioned 10 times in THUS SPAKE ZARATHUSTRA

10 | The biblical meaning of 10 is related to divine order, law, responsibility, and completeness. It also signifies creative power and authority on the Earth. The number 10 can indicate a reward or a judgment, as well as new beginnings. The 10 Commandments are a prominent example of the number 10 in the Bible.

‘SERPENT’ mentioned 31 times in THUS SPAKE ZARATHUSTRA

31 | XVII. (17) THE WAY OF THE CREATING ONE | Art thou a new strength and a new authority? A first motion? A self-rolling wheel? Canst thou also compel stars to revolve around thee?

Surprisingly, there are no months in the Hebrew calendar that contain 31 days, Five of them always have twenty-nine days, two can have twenty-nine or thirty, and the rest always contain thirty.

17 | In Hebrew ZY abridgment is 17 which also means victory. A symbol of spiritual weaponry. This weaponry ultimately leads to the conquering and overcoming of the spiritual world, resulting in victory from all the sadness of materialism and other evil world ruling powers. (On the 17th day of the first Hebrew month, Nisan, Jesus Christ was resurrected from the grave, death defeated.)

In this system, "Vāsudeva, literally, "the indwelling deity," is the first emanation and the fountainhead of the successive emanations, which may be represented either anthropomorphically or theriomorphically in Hindu art".

This is the Vaiśnava doctrine of Vyūha;

The doctrine of formation.

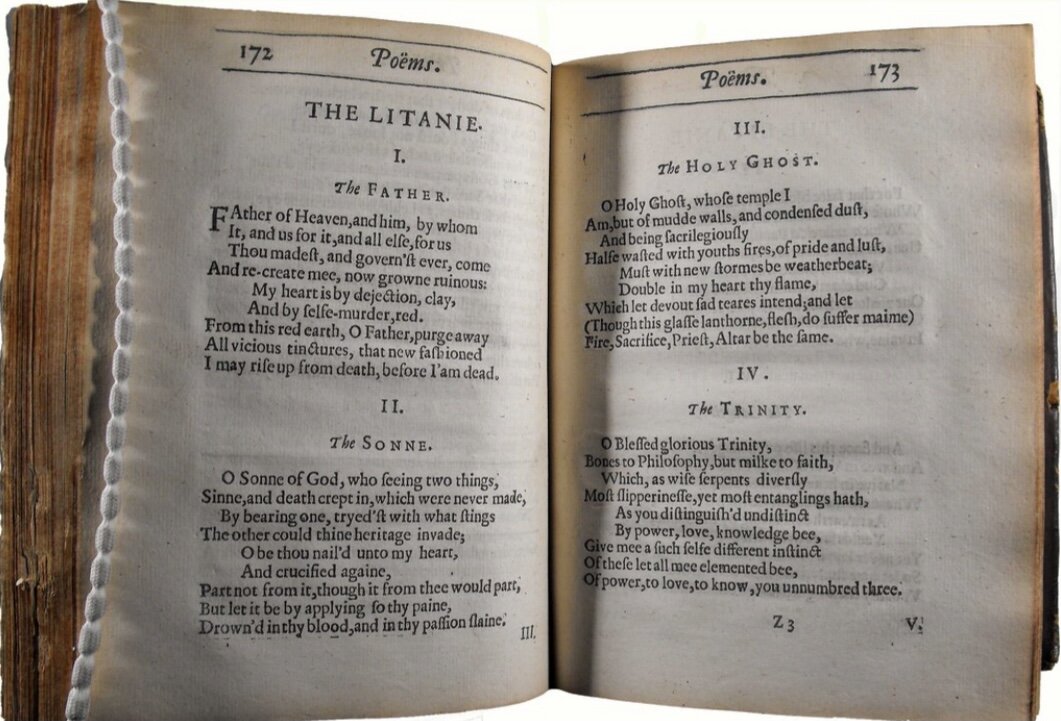

IV. TRINITY

O blessed glorious Trinity,

Bones to philosophy, but milk to faith,

Which, as wise serpents, diversely

Most slipperiness, yet most entanglings hath,

As you distinguish'd, undistinct,

By power, love, knowledge be,

Give me a such self-different instinct,

Of these let all me elemented be,

Of power, to love, to know you unnumbered three

John Donne, A Litany, 1896

Moral Destruction of American Prometheus

ONE OF THE MOST FAMOUS examples of Manhattan Project scientists’ moral conflicts is J. Robert Oppenheimer’s [1904 - 1967 (aged 62years)] invocation of lines from the Bhagavad Gita to describe the reaction to the Trinity Test. Trinity was the code name — chosen by Oppenheimer himself as a ode to a stanza by the same name in the poem ‘A Litany’ by John Donne — of the first detonation of a nuclear device. It was conducted by the United States Army at 5:29 a.m. on July 16, 1945, as part of the Manhattan Project in the Jornada del Muerto desert about 35 miles (56 km) southeast of Socorro, New Mexico. Oppenheimer goes on to muse;

WE KNEW THE WORLD WOULD NEVER BE THE SAME

A few people laughed, a few people cried, most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture the Bhagavad Gita. Vishnu is trying to persuade the prince that he should do his duty and, to impress him, takes on his multi-armed form and says:

‘Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.’

I supposed we all felt that,

one way or another.

In late October, 1945, Oppenheimer visited President Harry S. Truman (the driving force behind the Nuremberg Trials), who had okayed the use of both bombs, to talk to him about placing international controls on nuclear weapons. Truman, worried about the prospect of Soviet nuclear development, dismissed him. Two years after Trinity, Oppenheimer told physicists the bomb dramatized mercilessly the inhumanity and evil of modern war. He went on to note “the physicists have known sin; and this is a knowledge they cannot lose.” Perhaps not surprising when you name the detonation of the first nuclear weapon as the “bones to philosophy, but milk to faith.” And without even addressing its relation with faith it is indeed the bones to philosophy, responding to the ideas behind iis creation and use have reverberated through history since its inception, unfortunately these harmonics did not play in the trials of Nuremberg or Tokyo. It took a mere 17 years for the term ‘mutual assured destruction’ to be coined by Donald Brennan, a strategist working in Herman Kahn's Hudson Institute in 1962.

In a speech at the Princeton Theological Seminary (1958) he suggests a certain care is called for in thinking about the sciences and culture. The scientific age has an accumulative an irreversible character. It is a hallmark of science that is not shared by the arts. There is nothing irreversible about art, it won't go away but it's not primarily there as something for others to build upon, it's primarily there for the enjoyment insight and understanding. It is this irreversible character which means that in man's history, the sciences make changes which cannot be wished away and cannot be undone. The knowledge of how to make atomic bombs cannot be exorcised and one must bear in mind its virtual omnipresence character.

This is the will to truth, identified by Nietzsche, an ever accelerating and deepening chasm with which our society straddles. In science human progress is measured in a linear fashion, one may make a mistake, but that mistake is constituent of a null hypothesis.When one applies this to the human situation however, one will find no comparable moral progress. Yet one will find, moral injury.

Oppenheimer felt acutely that scientific and moral progress were analogous to each other, the former been vulnerable to a regression. Whereas scientific regression is not compatible with the very practising of science. Science and culture are not coextensive, they are not the same thing with different names. We live in a time with few historical parallels for while, to date, science has been yoked to the beating of culture, it has fast out paced the moral and ethical yardsticks with which measurement has traditionally taken place. The restructuring of human institutions, their obsolescence and inadequacy, and problems of the mind and spirit that come with such are the bones to philosophy, but milk to faith.